The idea of a Palestinian man or woman being openly gay and

accepted by the Palestinian community is somewhat of an oxymoron according to Tom Gross' Brutality Against Homosexuals in the Arab World. This idea is also suggested by Donna Rosenthal's chapter "Oy! Gay?" in her work The Israelis (2008). The complexity of Israeli society is demonstrated

by Rosenthal’s portrayal of gay and lesbian life in Israel. The

overall tolerance and acceptance of the homosexual community that Rosenthal depicts

is somewhat of a conundrum given the religious and cultural diversity of its population many of whom not only lack tolerance for

homosexuality, they see it as an abomination to their traditional cultural and religious values. Yet amid this diverse and multicultural society homosexual

rights are protected and safeguarded by the state of Israel—they can adopt, they can

claim property rights for their significant others and they can openly serve in

the military. Homosexuals have been given "special protection" per the 1998 sexual harassment law (371). So while traditional

cultures within Israel don’t accept their lifestyles, the Israeli state

demonstrates a tremendous amount of respect for the homosexuals right to live

freely and without fear of retribution or discrimination by the government.

According to Rosenthal, the Israeli government is so committed to this cause that we see the use of public service

ads that address the concerns of young men and women (teens) coming to terms

with their sexual identity. Rosenthal’s observation is further demonstrated by

the video below that portrays young Israeli men and women challenging

traditional gender roles and being comfortable crossing over to gay/transgender experience:

After watching this very colorful and upbeat public service message, one gets the sense that its not only okay, but "fun" to find out who you really are as a young person in Israel. But is it this true for all Israelis that want to "come out of the closet" and be who they really are? Is this true for Palestinians in Israel? For the Palestinians in the occupied territories? Rosenthal also explores the dark side to being gay in Israel by identifying the tensions that exist within the traditional communities in their

inability to come to terms with a gay son, daughter, spouse or other family

member. This dimension is clearly

outlined in the context of Palestinian Christian and Muslim homosexuals who find it nearly impossible to come out and face a culture that condemns homosexuality. The situation for gay Palestinian men and

women is even more severe in the occupied territories of the West Bank and Gaza. The initial question(s) this raises include: is gay life more difficult for Arab

Israelis? How does the Arab Israeli

conflict play into this discussion? What

about being Palestinian and gay in the occupied territories? What about those gay Palestinians seeking asylum in Israel?

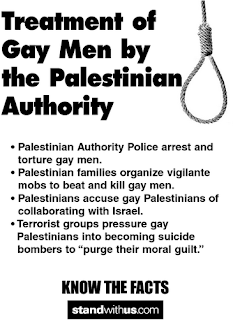

For Palestinians, being gay is akin to having the plague in a culture and religion that does not tolerate homosexuality. As Yossi Klein Halevi points out in The New Republic,

Islamic law prescribes five separate forms of death for homosexuals and on top of that, the Palestinian Authority adds several additional punishments for being gay. Halevi notes that the torment of gays is the official Palestinian policy of the PA.

In the West Bank city of Tulkarm, Halevi tells the story of a young Palestinian homosexual he calls Tayseer who discovered early on growing up in Gaza that being gay was the same as being a criminal. When he was arrested by an undercover police officer he was told that to avoid prison he would have to work as an undercover sex agent (entrapping other homosexuals). When he refused to cooperate he "was forced to stand in sewage up to his neck, his head covered by a sack filled with feces, and then he was thrown into a dark cell infested with insects and other creatures he could feel but not see... During one interrogation, police stripped him and forced him to sit on a Coke bottle. Throughout the entire ordeal he was taunted by interrogators, jailers, and fellow prisoners for being a homosexual." Tayseer is currently living as a refugee in an Arab Israeli village. Halevi tells another story of a Palestinian homosexual who was put in a pit in Nablus and starved to death over Ramadan; of another whose PA interrogators "cut him with glass and poured toilet cleaner into his wounds". One young man lives in constant fear that he will be killed by his family members. Such stories of torture and abuse by the PA makes Halevi wonder why more international attention hasn't been given to the plight of Palestinians living in the occupied territories.

In the West Bank city of Tulkarm, Halevi tells the story of a young Palestinian homosexual he calls Tayseer who discovered early on growing up in Gaza that being gay was the same as being a criminal. When he was arrested by an undercover police officer he was told that to avoid prison he would have to work as an undercover sex agent (entrapping other homosexuals). When he refused to cooperate he "was forced to stand in sewage up to his neck, his head covered by a sack filled with feces, and then he was thrown into a dark cell infested with insects and other creatures he could feel but not see... During one interrogation, police stripped him and forced him to sit on a Coke bottle. Throughout the entire ordeal he was taunted by interrogators, jailers, and fellow prisoners for being a homosexual." Tayseer is currently living as a refugee in an Arab Israeli village. Halevi tells another story of a Palestinian homosexual who was put in a pit in Nablus and starved to death over Ramadan; of another whose PA interrogators "cut him with glass and poured toilet cleaner into his wounds". One young man lives in constant fear that he will be killed by his family members. Such stories of torture and abuse by the PA makes Halevi wonder why more international attention hasn't been given to the plight of Palestinians living in the occupied territories.

Halevi's description of what he terms the Palestinian (gay) refugee problem is further demonstrated by the video clip below. This video conveys what life is like in Israel for gay Palestinians who flee the occupied territory. Specifically, the Palestinian teen in the video explains that he was jailed at the age of 12 for being gay (he had fled to Israel when discovered, but returned because he was home sick). The young man interviewed describes what life was like for him when he was jailed: he was constantly beaten and harassed. He was told that he had been "perverted by Israel".

Once he was released he fled to Israel and turned to prostitution to support himself. He has been living underground. The teen can't go back home, if discovered he would be deported by the Israeli authorities. He currently lives in Tel Aviv and seeks refuge in an unnamed community center, where the counselor named Shaoul explains that the young man is in an untenable situation: he can't go come because he will be killed by either the PA or his family and he can't come out of hiding or he will be deported where he is sure to be killed. The young man explains that he knew two boys that tried to go back and they were killed. The boy (now 16) says, "my dreams are simple: I want to be accepted". This situation stands in stark contrast to the videos depicting the happy go lucky gay teens who are free to be themselves and try on colorful clothing.

As the video suggests, the plight of the gay Palestinians has been addressed by community support groups in Israel. According to Rosenthal, the JOH, or the

Jersalem Open House makes a special effort to target their resources towards the Palestinians community (379). An interview with a JOH counselor below sheds life on the political, social and cultural difficulties faced by Palestinian gays:

The counselor notes, “your sexual identity develops

at the expense of your Palestinian identity” acknowledging that while the Israeli

community has a long way to go and the Palestinian community has an even farther

way to go in accepting homosexuals. Other stories further suggest

this notion.

The obstacles faced by Israel/Palestinian couples and its relationship to the Arab-Israeli conflict is also depicted in Rosenthal's book. For example, Rosenthal discusses a gay Israeli jew, Ezra who is fighting to get citizenship for his Muslim Palestinian partner, Selim. Selim served time in prison for his participation in the first intifada but now works with his lover in his plumbing business (380). She notes that many homosexual Palestinians are seeking political asylum in Israel (380).

Such gay love stories are also depicted in the film The Bubble (video clip on right) which shows the difficulties faced by Palestinian and Jewish Israeli gay couples that try to stay

together during this conflict (371). In the film, an Israeli national guardsman

Noam conspires to help his Palestinian lover Asraf stay in Tel Aviv. Like the teen depicted in the real-life video, Asraf is facing the problem of being gay, Palestinian and facing deportation to a territory (PA) that will undoubtedly condemn him to death. The Bubble demonstrates the harsh realities faced by homosexuals in Israel and the territories and how the conflict further exacerbates such difficulties. As Rosenthal suggests according to Arab culture "being called an 'int a luti' (you're a homosexual) is tantamount to being condemned to death" (376). In other words, being gay and Arab is somewhat of an oxymoron.

Such gay love stories are also depicted in the film The Bubble (video clip on right) which shows the difficulties faced by Palestinian and Jewish Israeli gay couples that try to stay

together during this conflict (371). In the film, an Israeli national guardsman

Noam conspires to help his Palestinian lover Asraf stay in Tel Aviv. Like the teen depicted in the real-life video, Asraf is facing the problem of being gay, Palestinian and facing deportation to a territory (PA) that will undoubtedly condemn him to death. The Bubble demonstrates the harsh realities faced by homosexuals in Israel and the territories and how the conflict further exacerbates such difficulties. As Rosenthal suggests according to Arab culture "being called an 'int a luti' (you're a homosexual) is tantamount to being condemned to death" (376). In other words, being gay and Arab is somewhat of an oxymoron.

Such gay love stories are also depicted in the film The Bubble (video clip on right) which shows the difficulties faced by Palestinian and Jewish Israeli gay couples that try to stay

together during this conflict (371). In the film, an Israeli national guardsman

Noam conspires to help his Palestinian lover Asraf stay in Tel Aviv. Like the teen depicted in the real-life video, Asraf is facing the problem of being gay, Palestinian and facing deportation to a territory (PA) that will undoubtedly condemn him to death. The Bubble demonstrates the harsh realities faced by homosexuals in Israel and the territories and how the conflict further exacerbates such difficulties. As Rosenthal suggests according to Arab culture "being called an 'int a luti' (you're a homosexual) is tantamount to being condemned to death" (376). In other words, being gay and Arab is somewhat of an oxymoron.

Such gay love stories are also depicted in the film The Bubble (video clip on right) which shows the difficulties faced by Palestinian and Jewish Israeli gay couples that try to stay

together during this conflict (371). In the film, an Israeli national guardsman

Noam conspires to help his Palestinian lover Asraf stay in Tel Aviv. Like the teen depicted in the real-life video, Asraf is facing the problem of being gay, Palestinian and facing deportation to a territory (PA) that will undoubtedly condemn him to death. The Bubble demonstrates the harsh realities faced by homosexuals in Israel and the territories and how the conflict further exacerbates such difficulties. As Rosenthal suggests according to Arab culture "being called an 'int a luti' (you're a homosexual) is tantamount to being condemned to death" (376). In other words, being gay and Arab is somewhat of an oxymoron.

No comments:

Post a Comment